Design Patterns

- Design Patterns - Structural Patterns

- Design Patterns - Behavioral Patterns

- Design Patterns - Creational patterns

- Concurrent Pattern

Design Patterns - Structural Patterns

Structural design patterns are design patterns that ease the design by identifying a simple way to realize relationships between entities.

Examples of Structural Patterns includes:

- Adapter pattern: ‘adapts’ one interface for a class into one that a client expects

- Bridge pattern: decouple an abstraction from its implementation so that the two can vary independently

- Composite pattern: a tree structure of objects where every object has the same interface

- Decorator pattern: add additional functionality to a class at runtime where subclassing would result in an exponential rise of new classes

- Proxy: Provide a placeholder for another object to control access to it.

- Front controller: The pattern relates to the design of Web applications. It provides a centralized entry point for handling requests.

- Facade pattern: Provide a unified interface to a set of interfaces in a subsystem. Facade defines a higher-level interface that makes the subsystem easier to use.

Adapter/Wrapper/Translator

The adapter pattern allows the interface of an existing class to be used as another interface. Note that: The interface may be incompatible but the inner function must suit the need.

implicit def adaptee2Adapter(adaptee: Adaptee): Adapter = {

new Adapter {

override def clientMethod: Unit = {

// call Adaptee's method(s) to implement Client's clientMethod */

}

}

}

Example in our code base: EhcacheManagerAdapter.scala

/**

* This class adapts an Ehcache cache manager to the [[CacheManager]] interface.

* @param underlyingManager Adapts this manager

*/

class EhcacheManagerAdapter(val underlyingManager: EhcacheManager) extends AbstractCacheManager {

}

/**

* An internal [[Cache]] implementation that adapts an ehcache cache

* to the [[Cache]] interface.

* @param underlyingCache The underlying ehcache cache object

* @tparam K Type of the key

* @tparam V Type of the value

*/

class EhcacheAdapter[K, V](manager: EhcacheManagerAdapter, val underlyingCache: Ehcache) extends Cache[K, V] {

}

Bridge

The bridge pattern decouples an abstraction from its implementation so that the two can vary independently. Note that:

The Bridge Pattern

- uses encapsulation, aggregation, and can use inheritance to separate responsibilities into different classes.

- is useful when both the class and what it does vary often.

- the class itself can be thought of as the abstraction and what the class can do as the implementation.

- can also be thought of as two layers of abstraction.

- is often confused with the adapter pattern. In fact, the bridge pattern is often implemented using the class adapter pattern.

- The implementation can be further decoupled to the point the abstraction is utilized.

trait DrawingAPI {

def drawCircle(x: Double, y: Double, radius: Double)

}

class DrawingAPI1 extends DrawingAPI {

def drawCircle(x: Double, y: Double, radius: Double) = println(s"API #1 $x $y $radius")

}

class DrawingAPI2 extends DrawingAPI {

def drawCircle(x: Double, y: Double, radius: Double) = println(s"API #2 $x $y $radius")

}

abstract class Shape(drawingAPI: DrawingAPI) {

def draw()

def resizePercentage(pct: Double)

}

class CircleShape(x: Double, y: Double, var radius: Double, drawingAPI: DrawingAPI)

extends Shape(drawingAPI: DrawingAPI) {

def draw() = drawingAPI.drawCircle(x, y, radius)

def resizePercentage(pct: Double) { radius *= pct }

}

object BridgePattern {

def main(args: Array[String]) {

Seq (

new CircleShape(1, 3, 5, new DrawingAPI1),

new CircleShape(4, 5, 6, new DrawingAPI2)

) foreach { x =>

x.resizePercentage(3)

x.draw()

}

}

}

Example in our code base: HeadcountForecastBridge.scala

public interface HeadcountForecastDAO{

...

}

// planLoader, scenarioLoader, serviceLocatorFactory are injected dependency which will change the implementation

// HeadcountForecastDAO interface is the abstract interface we can use

class HeadcountForecastBridge @Inject() (planLoader: PlanLoader, scenarioLoader: ScenarioLoader, serviceLocatorFactory: WFAServiceLocatorFactory)

extends HeadcountForecastDAO {

}

More examples

When:

----Shape---

/ \

Rectangle Circle

/ \ / \

BlueRectangle RedRectangle BlueCircle RedCircle

Refactor to:

----Shape--- Color

/ \ / \

Rectangle(Color) Circle(Color) Blue Red

Composite

The Composite Pattern is a partitioning design pattern which can be a tree structure of objects where every object has the same interface. A composite is an object designed as a composition of one-or-more similar objects, all exhibiting similar functionality. This is known as a “has-a” relationship between objects.

Motivation: When dealing with Tree-structured data, programmers often have to discriminate between a leaf-node and a branch. This makes code more complex, and therefore, error prone. The solution is an interface that allows treating complex and primitive objects uniformly.

Note: The operations you can perform on all the composite objects often have a least common denominator relationship. For example, it would be useful to define resizing a group of shapes to have the same effect (in some sense) as resizing a single shape.

trait Component { def operation(): Unit }

class Composite extends Component {

def operation() = children foreach { _.operation() }

def add(child: Component) = ...

def remove(child: Component) = ...

def getChild(index: Int) = ...

}

class Leaf extends Component {

def operation() = ...

}

trait Component{

def operation():Unit = this match {

case c:Composite => c.children.foreach(_.operation())

case leaf:Leaf => println("leaf")

}

}

object BridgePattern {

def main(args: Array[String]) {

val comp = new Composite()

comp += child1

comp += child2

comp -= child1

val firstChild = comp(0)

}

}

Example in our code base: The whole Internal DSL uses composite pattern, like ModelingSyntax.scala

def doubleMetricOf(const: Double): Exp[Metric[Double]]

def floor[T <: ModelTypes](metric: Exp[Metric[T]])

class ModelingArithmeticOps[T <: ModelTypes : TypeTag](metric: Exp[Metric[T]]) {

def +[F <: ModelTypes](addend: Exp[Metric[F]]): Exp[Metric[T]]

}

// floor(doubleMetricOf(1.5D)) + doubleMetricOf(2.0D) is of type Exp[Metric[Double]]

Decorator

The Decorator Pattern allows behavior to be added to an individual object, either statically or dynamically, without affecting the behavior of other objects from the same class.

Motivation: As an example, consider a window in a windowing system. Assume the window class has no functionality for adding scrollbars. One could create a subclass ScrollingWindow that provides them, or create a ScrollingWindowDecorator that adds this functionality to existing Window objects. At this point, either solution would be fine. This problem gets worse with every new feature or window subtype to be added.

class Coffee {

val sep = ", "

def cost:Double = 1

def ingredients: String = "Coffee"

}

trait Milk extends Coffee {

abstract override def cost = super.cost + 0.5

abstract override def ingredients = super.ingredients + sep + "Milk"

}

trait Whip extends Coffee {

abstract override def cost = super.cost + 0.7

abstract override def ingredients = super.ingredients + sep + "Whip"

}

trait Sprinkles extends Coffee {

abstract override def cost = super.cost + 0.2

abstract override def ingredients = super.ingredients + sep + "Sprinkles"

}

object DecoratorSample {

def main(args: Array[String]) {

var c: Coffee = new Coffee with Sprinkles

printf("Cost: %f Ingredients %s\n", c.cost, c.ingredients)

c = new Coffee with Sprinkles with Milk

printf("Cost: %f Ingredients %s\n", c.cost, c.ingredients)

c = new Coffee with Sprinkles with Milk with Whip

printf("Cost: %f Ingredients %s\n", c.cost, c.ingredients)

}

}

Proxy

A proxy is a wrapper or agent object that is being called by the client to access the real serving object behind the scenes. Use of the proxy can simply be forwarding to the real object, or can provide additional logic. Use it for lazy initialization, performance improvement by caching the object and controlling access to the client/caller

trait Proxy

trait Service

trait ImageProvider {

val fileUrl: URL

def image: ImageIcon

}

private class RealImageService(val fileUrl: URL) extends Service with ImageProvider {

private val imageIcon = new ImageIcon(fileUrl)

def image: ImageIcon = imageIcon

}

class ImageServiceProxy(imageFileUrl: URL) extends Proxy with ImageProvider {

val fileUrl = imageFileUrl

private lazy val imageService = new RealImageService(imageFileUrl)

def image: ImageIcon = imageService.image

override def toString = "ImageServiceProxy for: " + imageFileUrl.toString()

}

Front controller

The front controller design pattern means that all requests that come for a resource in an application will be handled by a single handler and then dispatched to the appropriate handler for that type of request.

public class HomeView {

public void show(){

System.out.println("Displaying Home Page");

}

}

public class StudentView {

public void show(){

System.out.println("Displaying Student Page");

}

}

public class Dispatcher {

private StudentView studentView;

private HomeView homeView;

public Dispatcher(){

studentView = new StudentView();

homeView = new HomeView();

}

public void dispatch(String request){

if(request.equalsIgnoreCase("STUDENT")){

studentView.show();

}

else{

homeView.show();

}

}

}

public class FrontController {

private Dispatcher dispatcher;

public FrontController(){

dispatcher = new Dispatcher();

}

private boolean isAuthenticUser(){

System.out.println("User is authenticated successfully.");

return true;

}

private void trackRequest(String request){

System.out.println("Page requested: " + request);

}

public void dispatchRequest(String request){

//log each request

trackRequest(request);

//authenticate the user

if(isAuthenticUser()){

dispatcher.dispatch(request);

}

}

}

public class FrontControllerPatternDemo {

public static void main(String[] args) {

FrontController frontController = new FrontController();

frontController.dispatchRequest("HOME");

frontController.dispatchRequest("STUDENT");

}

}

Difference between Frontend-Controller and Router:

A Frontend-Controller should collaborate with a Router and a Dispatcher to decide based on the (HTTP) request against the application which concrete Action has to be executed and then dispatches it.

So the routing takes care of or helps with identifying which action method to execute and the controller then is responsible to provide this action but both handle the request.

In our code base, the Frontend Controller Pattern is handled by play framework. But the following code has similar idea:

class AnalysisController @Inject() (environmentManager: EnvironmentManager,

serviceLocatorFactory: BaseServiceLocatorFactory,

actionProvider: ActionProvider)

extends Controller(environmentManager, serviceLocatorFactory) {

// ... Some common logic all requests handler share

def performAnalysisChartAction(analysisId: String, chartId: String, command: String): AnyAction = dispatcher(command) {

case ANALYSIS_CHART_RENDER => ... RenderChart.create(analysisId, chartId) ...

case ANALYSIS_CHART_RESIZE => ...

case ANALYSIS_CAPTURE_CHART => ...

...

}

}

Above code provides a centralized controller to handle chart rendering request of different commands. By doing such, avoid the duplicated code of some common logic that all requests handler share.

Facade pattern

A Facade is used when an easier or simpler interface to an underlying object is desired. Alternatively, an adapter can be used when the wrapper must respect a particular interface and must support polymorphic behavior. A decorator makes it possible to add or alter behavior of an interface at run-time.

| Pattern | Intent |

|---|---|

| Adapter | Converts one interface to another so that it matches what the client is expecting |

| Decorator | Dynamically adds responsibility to the interface by wrapping the original code |

| Facade | Provides a simplified interface |

The facade pattern is typically used when:

- a simple interface is required to access a complex system;

- the abstractions and implementations of a subsystem are tightly coupled;

- need an entry point to each level of layered software; or

- a system is very complex or difficult to understand.

Code Example:

trait SubSystemA {

def methodA1()

def methodA2()

}

trait SubSystemB {

def methodB()

}

class ConcreteSubSystemA extends SubSystemA {

override def methodA1() {

println("System A: method1")

}

override def methodA2() {

println("System A: method2")

}

}

class ConcreteSubSystemB extends SubSystemB {

override def methodB() {

println("System B: method")

}

}

class Facade extends SubSystemA with SubSystemB {

val subsystemA = new ConcreteSubSystemA()

val subsystemB = new ConcreteSubSystemB()

override def methodA1() {

subsystemA.methodA1()

}

override def methodA2() {

subsystemA.methodA2()

}

override def methodB() {

subsystemB.methodB()

}

}

// Client

object FacadeClient extends Application {

var facade = new Facade()

facade.methodA1()

facade.methodA2()

facade.methodB()

}

Note: how to force the order of function call when implement a facade method:

trait facadeTrait {

def functionA(): ResultA

def functionB(result: ResultA): ResultB

def functionC(result: ResultB): ResultC

}

Design Patterns - Behavioral Patterns

Behavioral Design Patterns are design patterns that identify common communication patterns between objects and realize these patterns. By doing so, these patterns increase flexibility in carrying out this communication.

Examples of Behavioral Patterns includes:

- Chain-of-responsibility Pattern: Command objects are handled or passed on to other objects by logic-containing processing objects

- Command Pattern: Command objects encapsulate an action and its parameters

- Interpreter Pattern: Implement a specialized computer language to rapidly solve a specific set of problems

- Mediator pattern: Define an object that encapsulates how a set of objects interact. Mediator promotes loose coupling by keeping objects from referring to each other explicitly, and it allows their interaction to vary independently.

- Observer: Define a one-to-many dependency between objects where a state change in one object results in all its dependents being notified and updated automatically.

- Visitor: Represent an operation to be performed on the elements of an object structure. Visitor lets a new operation be defined without changing the classes of the elements on which it operates.

- Strategy pattern: Define a family of algorithms, encapsulate each one, and make them interchangeable. Strategy lets the algorithm vary independently from clients that use it.

Chain-of-responsibility Pattern

Chain-of-responsibility Pattern consists of a source of command objects and a series of processing objects. Each processing object contains logic that defines the types of command objects that it can handle; the rest are passed to the next processing object in the chain.

Example would be the mechanism of exception handling. A source of command objects is the exception object and a series of processing objects are exception handlers at each level.

Note: the source don’t know who should handle until the runtime.

In scala, the pattern matching use Chain-of-responsibility Pattern.

parentClassInstance match{

case instance: SubClass1 =>

case instance: SubClass2 =>

}

More examples for Chain-of-responsibility pattern in scala:

case class Event(level: Int, title: String)

//Base handler class

abstract class Handler {

val successor: Option[Handler]

def handleEvent(event: Event): Unit

}

//Customer service agent

class Agent(val successor: Option[Handler]) extends Handler {

override def handleEvent(event: Event): Unit = {

event match {

case e if e.level < 2 => println("CS Agent Handled event: " + e.title)

case e if e.level > 1 => {

successor match {

case Some(h: Handler) => h.handleEvent(e)

case None => println("Agent: This event cannot be handled.")

}

}

}

}

}

class Supervisor(val successor: Option[Handler]) extends Handler {

override def handleEvent(event: Event): Unit = {

event match {

case e if e.level < 3 => println("Supervisor handled event: " + e.title)

case e if e.level > 2 => {

successor match {

case Some(h: Handler) => h.handleEvent(e)

case None => println("Supervisor: This event cannot be handled")

}

}

}

}

}

class Boss(val successor: Option[Handler]) extends Handler {

override def handleEvent(event: Event): Unit = {

event match {

case e if e.level < 4 => println("Boss handled event: " + e.title)

case e if e.level > 3 => successor match {

case Some(h: Handler) => h.handleEvent(e)

case None => println("Boss: This event cannot be handled")

}

}

}

}

object Main {

def main(args: Array[String]) {

val boss = new Boss(None)

val supervisor = new Supervisor(Some(boss))

val agent = new Agent(Some(supervisor))

println("Passing events")

val events = Array(

Event(1, "Technical support"),

Event(2, "Billing query"),

Event(1, "Product information query"),

Event(3, "Bug report"),

Event(5, "Police subpoena"),

Event(2, "Enterprise client request")

)

events foreach { e: Event =>

agent.handleEvent(e)

}

}

}

In our code base: getScope will chain a sequence of scope, but who should be responsiblity to handle, we do not know in advance.

Chain-of-responsibility is widely used in front-end. Ex. UI components form a chain. We will iterate through the chain to discover who should be responsible to it.

Command Pattern

Command Pattern encapsulates all information needed to perform an action or trigger an event at a later time. This information includes the method name, the object that owns the method and values for the method parameters.

In Scala, we can rely on by-name parameter to defer evaluation of any expression:

object Invoker {

private var history: Seq[() => Unit] = Seq.empty

def invoke(command: => Unit) { // by-name parameter

command

history :+= command _

}

}

Invoker.invoke(println("foo"))

Invoker.invoke {

println("bar 1")

println("bar 2")

}

The idea is to store function and parameters as an object and to execute it later.

abstract class CommandBase{

def undo: Unit

def redo: Unit

}

class MoveCommand extends CommandBase{

override def undo: Unit = ???

override def redo: Unit = ???

}

class DeleteCommand extends CommandBase{

override def undo: Unit = ???

override def redo: Unit = ???

}

val undoStack: List[CommandBase] = ???

val redoStack: List[CommandBase] = ???

Interpreter Pattern

Interpreter Pattern is a design pattern that specifies how to evaluate sentences in a language. The basic idea is to have a class for each symbol (terminal or nonterminal) in a specialized computer language. The syntax tree of a sentence in the language is an instance of the composite pattern and is used to evaluate (interpret) the sentence for a client.

case class Context

abstract class AbstractExpression{

def interpret(Context context): Unit

}

class TerminalExpression extends AbstractExpression{

override def interpret(Context context): Unit = ???

}

class NonTerminalExpression(expressions: AbstractExpression*) extends AbstractExpression{

override def interpret(Context context): Unit = ???

}

def main(): Unit = {

val context = Context

val expressionTree = List(

new TerminalExpression,

new NonTerminalExpression(

new NonTerminalExpression(new TerminalExpression),

new TerminalExpression))

expressionTree.foreach{ expression =>

expression.interpret(context)

}

}

Example in our code base: The whole Internal DSL uses Composite Pattern and Interpreter Pattern, like ModelingSyntax.scala

def doubleMetricOf(const: Double): Exp[Metric[Double]]

def floor[T <: ModelTypes](metric: Exp[Metric[T]])

class ModelingArithmeticOps[T <: ModelTypes : TypeTag](metric: Exp[Metric[T]]) {

def +[F <: ModelTypes](addend: Exp[Metric[F]]): Exp[Metric[T]]

}

// floor(doubleMetricOf(1.5D)) + doubleMetricOf(2.0D) is of type Exp[Metric[Double]]

/**

* Prepare the data structures required to evaluate the model.

*

* @return PerThreadInitialization case class (see above)

*/

def interpretExpTree: ExpTreeInterpretation = {

val ExpTreeInitialization(expTree, substitutions) = initializeExpTree

// invoke the interpreter to get the 'prepared calculation' using the input calculations we just made

val prepared = Interpreter.interpretPlan(expTree, substitutions, PrepareModel.evaluator, new ContextVars {}, Seq.empty)

...

}

Mediator

Usually a program is made up of a large number of classes. So the logic and computation is distributed among these classes. The problem of communication between these classes may become more complex .

With the mediator pattern, communication between objects is encapsulated with a mediator object. Objects no longer communicate directly with each other, but instead communicate through the mediator.

The following example use ChatRoom as a mediator to help each User’s communicate with each other.

public class ChatRoom {

public static void showMessage(User user, String message){

System.out.println(new Date().toString() + " [" + user.getName() + "] : " + message);

}

}

public class User {

private String name;

public String getName() {

return name;

}

public void setName(String name) {

this.name = name;

}

public User(String name){

this.name = name;

}

public void sendMessage(String message){

ChatRoom.showMessage(this,message);

}

}

public class MediatorPatternDemo {

public static void main(String[] args) {

User robert = new User("Robert");

User john = new User("John");

robert.sendMessage("Hi! John!");

john.sendMessage("Hello! Robert!");

}

}

Observer

Observer pattern is used when there is one-to-many relationship between objects such as if one object is modified, its depenedent objects are to be notified automatically.

In the following example, Subject class has a list of Observer’s acted as subscribers; once the Observer’s state has changed, all of its subscribers will be notified.

public abstract class Observer {

protected Subject subject;

public abstract void update();

}

public class BinaryObserver extends Observer{

public BinaryObserver(Subject subject){

this.subject = subject;

this.subject.attach(this);

}

@Override

public void update() {

System.out.println( "Binary String: " + Integer.toBinaryString( subject.getState() ) );

}

}

public class OctalObserver extends Observer{

public OctalObserver(Subject subject){

this.subject = subject;

this.subject.attach(this);

}

@Override

public void update() {

System.out.println( "Octal String: " + Integer.toOctalString( subject.getState() ) );

}

}

public class HexaObserver extends Observer{

public HexaObserver(Subject subject){

this.subject = subject;

this.subject.attach(this);

}

@Override

public void update() {

System.out.println( "Hex String: " + Integer.toHexString( subject.getState() ).toUpperCase() );

}

}

public class Subject {

private List<Observer> observers = new ArrayList<Observer>();

private int state;

public int getState() {

return state;

}

public void setState(int state) {

this.state = state;

notifyAllObservers();

}

public void attach(Observer observer){

observers.add(observer);

}

public void notifyAllObservers(){

for (Observer observer : observers) {

observer.update();

}

}

}

public class ObserverPatternDemo {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Subject subject = new Subject();

new HexaObserver(subject);

new OctalObserver(subject);

new BinaryObserver(subject);

System.out.println("First state change: 15");

subject.setState(15);

System.out.println("Second state change: 10");

subject.setState(10);

}

}

Visitor

The visitor design pattern is a way of separating an algorithm from an object structure on which it operates.

/*

ComputerParts

*/

public interface ComputerPart {

public void accept(ComputerPartVisitor computerPartVisitor);

}

public class Keyboard implements ComputerPart {

@Override

public void accept(ComputerPartVisitor computerPartVisitor) {

computerPartVisitor.visit(this);

}

}

public class Monitor implements ComputerPart {

@Override

public void accept(ComputerPartVisitor computerPartVisitor) {

computerPartVisitor.visit(this);

}

}

public class Mouse implements ComputerPart {

@Override

public void accept(ComputerPartVisitor computerPartVisitor) {

computerPartVisitor.visit(this);

}

}

public class Computer implements ComputerPart {

ComputerPart[] parts;

public Computer(){

parts = new ComputerPart[] {new Mouse(), new Keyboard(), new Monitor()};

}

@Override

public void accept(ComputerPartVisitor computerPartVisitor) {

for (int i = 0; i < parts.length; i++) {

parts[i].accept(computerPartVisitor);

}

computerPartVisitor.visit(this);

}

}

/*

ComputerPartVisitor

*/

public interface ComputerPartVisitor {

public void visit(Computer computer);

public void visit(Mouse mouse);

public void visit(Keyboard keyboard);

public void visit(Monitor monitor);

}

public class ComputerPartDisplayVisitor implements ComputerPartVisitor {

@Override

public void visit(Computer computer) {

System.out.println("Displaying Computer.");

}

@Override

public void visit(Mouse mouse) {

System.out.println("Displaying Mouse.");

}

@Override

public void visit(Keyboard keyboard) {

System.out.println("Displaying Keyboard.");

}

@Override

public void visit(Monitor monitor) {

System.out.println("Displaying Monitor.");

}

}

public class VisitorPatternDemo {

public static void main(String[] args) {

ComputerPart computer = new Computer();

computer.accept(new ComputerPartDisplayVisitor());

}

}

Advantage of above code:

- add a new ComputerPart will not affect existing one

- implement a new visitor will not affect the behaviour of existing visitors

Disadvantage:

- add a new ComputerPart is esay. However, need to implement visit(ComputerPart) for each existing visitors.

Code Example from code base:

trait MemberSetVisitor[T] {

def visit(set: MemberSet): T = throw new EngineException(RCIE000033, VEE_UNSUPPORTED)

def visit(set: EmptySet): T

def visit(set: DefaultMembers): T

def visit(set: RootMembers): T

def visit(set: ChildMembers): T

def visit(set: SpecificMembers): T

def visit(set: DescendantsByLevel): T

def visit(set: Crossjoin): T

}

case class Crossjoin(

val sets: Seq[MemberSet],

val typeId: String = MemberSetTypes.FUNCTION,

val functionId: String = FunctionNames.CROSSJOIN)

extends FunctionMemberSet {

// ??????, should all underlying sets accept the visitor, then visit itself?

def accept[T](visitor: MemberSetVisitor[T]): T = visitor.visit(this)

}

class AsSimpleQueryBuilderVisitor(queryMetric: Metric,

context: MemberSetContext,

interpreter: DataDslInterpreter)

(implicit model: DataDslModel)

extends MemberSetVisitor[SimpleQueryBuilder]{

override def visit(set: EmptySet): SimpleQueryBuilder = model.newQueryBuilder(queryMetric)

override def visit(set: Crossjoin): SimpleQueryBuilder = {

set.sets.foldLeft(model.newQueryBuilder(queryMetric)) { (result, set) =>

// ??????, why accept inside visit methods? Should the element knows how its children are constructed?

// Maybe we want to visit things differently among visitors?

val builder = set.accept(this)

...

}

...

}

The above code is actually a bad example. Because, web request may have different types: GET, PUT, POST, DELETE. Centrallized the control logic will cause the trouble of narrow our request type to one single type. For example, render chart, save chart, resize chart all use the POST type.

Visitor Pattern VS Pattern Matching

interview with Martin Odersky (creator of Scala Language)

So the right tool for the job really depends on which direction you want to extend. If you want to extend with new data, you pick the classical object-oriented approach with virtual methods. If you want to keep the data fixed and extend with new operations, then patterns are a much better fit. There’s actually a design pattern—not to be confused with pattern matching—in object-oriented programming called the visitor pattern, which can represent some of the things we do with pattern matching in an object-oriented way, based on virtual method dispatch. But in practical use the visitor pattern is very bulky. You can’t do many of the things that are very easy with pattern matching. You end up with very heavy visitors. And it also turns out that with modern VM technology it’s way more innefficient than pattern matching. For both of these reasons, I think there’s a definite role for pattern matching.

Example: consider how complicated just to implement the following use Visitor Pattern; Basically, you need to create an abstract class for visitor, and create concrete class for each operation and its getters and setters as well.

sealed abstract class Expr

case class Num(n: Int) extends Expr

case class Sum(l: Expr, r: Expr) extends Expr

case class Prod(l: Expr, r: Expr) extends Expr

def evalExpr(e: Expr): Int = e match {

case Num(n) => n

case Sum(l, r) => evalExpr(l) + evalExpr(r)

case Prod(l, r) => evalExpr(l) * evalExpr(r)

}

def printExpr(e: Expr) = e match {

case Num(n) => print(" " + n + " ")

case Sum(l, r) => printExpr(l); print("+"); printExpr(r)

case Prod(l, r) => printExpr(l); print("x"); printExpr(r)

}

Strategy pattern

Strategy pattern (also known as the policy pattern) is a software design pattern that enables an algorithm’s behavior to be selected at runtime.

For instance, a class that performs validation on incoming data may use a strategy pattern to select a validation algorithm based on the type of data, the source of the data, user choice, or other discriminating factors. These factors are not known for each case until run-time, and may require radically different validation to be performed.

Think twice before implementing this pattern. You have to be sure your need is to frequently change an algorithm. You have to clearly anticipate the future, otherwise, this pattern will be more expensive than a basic implementation. This pattern is expensive to create. This pattern can be expensive to maintain. If the representation of a class often changes, you will have lots of refactoring. This pattern is hard to remove too.

| Pattern | Intent |

|---|---|

| State | can activate several states, whereas a strategy can only activate one of the algorithms. |

| Flyweight | provides a shared object that can be used in multiple contexts simultaneously, whereas a strategy focuses on one context |

| Decorator | changes the skin of an object, whereas a strategy changes the guts of an object |

| Composite | is used in combination with a strategy to improve efficiency |

Code Example:

class SomeParam

class SomeReturnValue

object Strategies {

def strategyA(param:SomeParam) : SomeReturnValue = {

println("strategy A")

return new SomeReturnValue()

}

def strategyB(param:SomeParam) : SomeReturnValue = {

println("strategy B")

return new SomeReturnValue()

}

def strategyC(param:SomeParam) : SomeReturnValue = {

println("strategy C")

return new SomeReturnValue()

}

}

class MyApplication(var strategy: (SomeParam => SomeReturnValue)) {

def doSomething(param:SomeParam) : SomeReturnValue = {

return strategy(param)

}

}

// Client

object StrategyClient extends Application {

var arg = "a"

var strategy:(SomeParam => SomeReturnValue) = _

arg match {

case "a" => strategy = Strategies.strategyA

case "b" => strategy = Strategies.strategyB

case _ => strategy = Strategies.strategyC

}

var myapp = new MyApplication(strategy)

myapp.doSomething(new SomeParam())

myapp.strategy = Strategies.strategyC

myapp.doSomething(new SomeParam())

}

Design Patterns - Creational patterns

Creational patterns are design patterns that deal with object creation mechanisms, trying to create objects in a manner suitable to the situation. Examples:

- Lazy initialization: Tactic of delaying the creation of an object, the calculation of a value, or some other expensive process until the first time it is needed.

- Singleton: Ensure a class has only one instance, and provide a global point of access to it.

- Factory: Define an interface for creating a single object, but let subclasses decide which class to instantiate. Factory Method lets a class defer instantiation to subclasses.

- Abstract factory: Provides a way to encapsulate a group of individual factories that have a common theme without specifying their concrete classes.

Lazy initialization

Lazy initialization is the tactic of delaying the creation of an object, the calculation of a value, or some other expensive process until the first time it is needed.

In a software design pattern view, lazy initialization is often used together with a factory method pattern, so called the “lazy factory”. This combines three ideas:

- Using a factory method to get instances of a class (factory method pattern)

- Store the instances in a map, so you get the same instance the next time you ask for an instance with same parameter (multiton pattern)

- Using lazy initialization to instantiate the object the first time it is requested (lazy initialization pattern)

In scala, the support for lazy value is built-in:

class Example {

lazy val x = "Value";

}

Above code is compiled to the code equivalent to the following java code:

public class Example {

private String x;

private volatile boolean bitmap$0;

public String x() {

if(this.bitmap$0 == true) {

return this.x;

} else {

return x$lzycompute();

}

}

private String x$lzycompute() {

synchronized(this) {

if(this.bitmap$0 != true) {

this.x = "Value";

this.bitmap$0 = true;

}

return this.x;

}

}

}

However, using lazy val could be troublesome.

Scenario1: Potential dead lock when accessing lazy vals

import scala.concurrent.ExecutionContext.Implicits.global

import scala.concurrent._

import scala.concurrent.duration._

object A {

lazy val base = 42

lazy val start = B.step

}

object B {

lazy val step = A.base

}

object Scenario1 {

def run = {

val result = Future.sequence(Seq(

Future { A.start }, // (1)

Future { B.step } // (2)

))

Await.result(result, 1.minute)

}

}

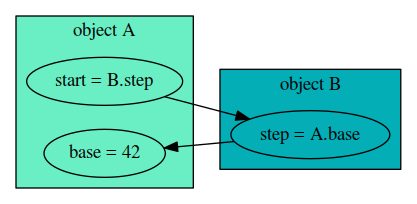

As the following figure illustrates:

The A.start val depends on B.step which in turn depends again on A.base. Although there is no cyclic relation here, running this code can lead to a deadlock:

scala> :paste

...

scala> Scenario1.run

java.util.concurrent.TimeoutException: Futures timed out after [1 minute]

at scala.concurrent.impl.Promise$DefaultPromise.ready(Promise.scala:219)

at scala.concurrent.impl.Promise$DefaultPromise.result(Promise.scala:223)

at scala.concurrent.Await$$anonfun$result$1.apply(package.scala:190)

at scala.concurrent.BlockContext$DefaultBlockContext$.blockOn(BlockContext.scala:53)

at scala.concurrent.Await$.result(package.scala:190)

at Scenario2$.run(<console>:30)

... 32 elided

Reason: when scala lazy val is compiled to java code, synchronized block is used, which will lock the current object.

- Thread 1 is holding A at

(1)while try to access B; - Thread 2 is holding B at

(2)while try to access A.

Thus deadlock occurs.

Scenario 2: Deadlock in combination with synchronization

import scala.concurrent.ExecutionContext.Implicits.global

import scala.concurrent._

import scala.concurrent.duration._

trait Compute {

def compute: Future[Int] =

Future(this.synchronized { 21 + 21 }) // (1)

}

object Scenario2 extends Compute {

def run: Unit = {

lazy val someVal: Int =

Await.result(compute, 1.minute) // (2)

println(someVal)

}

}

After execute above code in scala, we will get the following error

scala> :paste

...

scala> Scenario2.run

java.util.concurrent.TimeoutException: Futures timed out after [1 minute]

at scala.concurrent.impl.Promise$DefaultPromise.ready(Promise.scala:219)

at scala.concurrent.impl.Promise$DefaultPromise.result(Promise.scala:223)

at scala.concurrent.Await$$anonfun$result$1.apply(package.scala:190)

at scala.concurrent.BlockContext$DefaultBlockContext$.blockOn(BlockContext.scala:53)

at scala.concurrent.Await$.result(package.scala:190)

at Scenario2$.someVal$lzycompute$1(<console>:30)

at Scenario2$.someVal$1(<console>:29)

at Scenario2$.run(<console>:31)

... 32 elided

Reason: Same as in scenario 1, when synchronized block is used, current object will be locked to prevent other thread from access it.

When call println, lazy initialization of someVal is triggered, and lock the current object; However, in order to calculate the result of compute, the current object also needs to be locked. Thus deadlock occurs.

Example 3: Order of initilization

Below code will get Null Pointer Exception. Because the Dervied, Base and Sub is initilized in order.

trait Base{

val value: String

}

trait Sub{ self: Base =>

val value2 = value.length

}

class Derived extends Base with Sub{

override val value = "abc"

}

Below improved code still not work.

trait Base{

val value: String

}

trait Sub extends Base {

override val value2 = value.length

}

class Derived extends Sub{

override val value = "abc"

}

The way we can fix it is to use the following:

trait Base{

val value: String

}

trait Sub{ self: Base =>

lazy val value2 = value.length

}

class Derived extends Base with Sub{

override val value = "abc"

}

Singleton

The singleton pattern is a design pattern that restricts the instantiation of a class to one object.

In java, initialization of singleton use eager initialization:

/* Singleton implementation without lazy initialisation */

public class Singleton {

// Eager initialization

private static final Singleton INSTANCE = new Singleton();

private Singleton() { /* Initialisation code */ }

public static Singleton getInstance() {

return INSTANCE;

}

}

In scala, it’s as easy as create an object

trait Service

object Singleton extend Service{

...

}

functionTakesInAService(service = Singleton)

How to extend the functionality of a singleton object in scala:

object X{

def x = 5

}

object Y{

import X._

val y = x

}

But most of the time, it’s better to composite an object instead of extend an object.

Factory

“Define an interface for creating an object, but let subclasses decide which class to instantiate. The Factory method lets a class defer instantiation it uses to subclasses.” (Gang Of Four)

The following two scenarios can both be treated as Facotry Pattern

-

Create a common interface at compilation time, and determine which which implementation at runtime

-

Create a common base class at compilation time, and determine which derived class to use (based on which method be override) at runtime

Problems:

-

Determine at runtime.

-

Weak base class problems.

Example:

public interface Shape {

void draw();

}

public class Rectangle implements Shape {

@Override

public void draw() {

System.out.println("Inside Rectangle::draw() method.");

}

}

public class Square implements Shape {

@Override

public void draw() {

System.out.println("Inside Square::draw() method.");

}

}

public class Circle implements Shape {

@Override

public void draw() {

System.out.println("Inside Circle::draw() method.");

}

}

public class ShapeFactory {

//use getShape method to get object of type shape

public Shape getShape(String shapeType){

if(shapeType == null){

return null;

}

if(shapeType.equalsIgnoreCase("CIRCLE")){

return new Circle();

} else if(shapeType.equalsIgnoreCase("RECTANGLE")){

return new Rectangle();

} else if(shapeType.equalsIgnoreCase("SQUARE")){

return new Square();

}

return null;

}

}

public class FactoryPatternDemo {

public static void main(String[] args) {

ShapeFactory shapeFactory = new ShapeFactory();

//get an object of Circle and call its draw method.

Shape shape1 = shapeFactory.getShape("CIRCLE");

//call draw method of Circle

shape1.draw();

//get an object of Rectangle and call its draw method.

Shape shape2 = shapeFactory.getShape("RECTANGLE");

//call draw method of Rectangle

shape2.draw();

//get an object of Square and call its draw method.

Shape shape3 = shapeFactory.getShape("SQUARE");

//call draw method of circle

shape3.draw();

}

}

Abstract Factory

Abstract Factory patterns work around a super-factory which creates other factories. This factory is also called as factory of factories.

Shape Interface:

public interface Shape {

void draw();

}

public class Rectangle implements Shape {

@Override

public void draw() {

System.out.println("Inside Rectangle::draw() method.");

}

}

public class Square implements Shape {

@Override

public void draw() {

System.out.println("Inside Square::draw() method.");

}

}

public class Circle implements Shape {

@Override

public void draw() {

System.out.println("Inside Circle::draw() method.");

}

}

Color Interface:

public interface Color {

void fill();

}

public class Red implements Color {

@Override

public void fill() {

System.out.println("Inside Red::fill() method.");

}

}

public class Green implements Color {

@Override

public void fill() {

System.out.println("Inside Green::fill() method.");

}

}

public class Blue implements Color {

@Override

public void fill() {

System.out.println("Inside Blue::fill() method.");

}

}

The Abstract Factory Interface:

public abstract class AbstractFactory {

abstract Color getColor(String color);

abstract Shape getShape(String shape) ;

}

The Shape Factory:

public class ShapeFactory extends AbstractFactory {

@Override

public Shape getShape(String shapeType){

if(shapeType == null){

return null;

}

if(shapeType.equalsIgnoreCase("CIRCLE")){

return new Circle();

}else if(shapeType.equalsIgnoreCase("RECTANGLE")){

return new Rectangle();

}else if(shapeType.equalsIgnoreCase("SQUARE")){

return new Square();

}

return null;

}

@Override

Color getColor(String color) {

return null;

}

}

The color Factory

public class ColorFactory extends AbstractFactory {

@Override

public Shape getShape(String shapeType){

return null;

}

@Override

Color getColor(String color) {

if(color == null){

return null;

}

if(color.equalsIgnoreCase("RED")){

return new Red();

}else if(color.equalsIgnoreCase("GREEN")){

return new Green();

}else if(color.equalsIgnoreCase("BLUE")){

return new Blue();

}

return null;

}

}

Factory Producer

public class FactoryProducer {

public static AbstractFactory getFactory(String choice){

if(choice.equalsIgnoreCase("SHAPE")){

return new ShapeFactory();

}else if(choice.equalsIgnoreCase("COLOR")){

return new ColorFactory();

}

return null;

}

}

Abstract Factory Demo

public class AbstractFactoryPatternDemo {

public static void main(String[] args) {

//get shape factory

AbstractFactory shapeFactory = FactoryProducer.getFactory("SHAPE");

//get an object of Shape Circle

Shape shape1 = shapeFactory.getShape("CIRCLE");

//call draw method of Shape Circle

shape1.draw();

//get an object of Shape Rectangle

Shape shape2 = shapeFactory.getShape("RECTANGLE");

//call draw method of Shape Rectangle

shape2.draw();

//get an object of Shape Square

Shape shape3 = shapeFactory.getShape("SQUARE");

//call draw method of Shape Square

shape3.draw();

//get color factory

AbstractFactory colorFactory = FactoryProducer.getFactory("COLOR");

//get an object of Color Red

Color color1 = colorFactory.getColor("RED");

//call fill method of Red

color1.fill();

//get an object of Color Green

Color color2 = colorFactory.getColor("Green");

//call fill method of Green

color2.fill();

//get an object of Color Blue

Color color3 = colorFactory.getColor("BLUE");

//call fill method of Color Blue

color3.fill();

}

}

Concurrent Pattern

Concurrency patterns are those types of design patterns that deal with the multi-threaded programming paradigm. Examples of this class of patterns include:

- Binding Properties Pattern: Combining multiple observers to force properties in different objects to be synchronized or coordinated in some way.

- Asynchronous method invocation: Asynchronous pattern is a client-side support that doesn’t block the calling thread while waiting for a reply. Instead, the calling thread is notified when the reply arrives.

Binding Properties Pattern

The Binding properties pattern is combining multiple observers to force properties in different objects to be synchronized or coordinated in some way.

There is a digest cycle, where the scope examines all of the $watch expressions and compares them with the previous value. It looks at the object models for changes, if the old value isn’t the same as the new value, AngularJS will update the appropriate places, a.k.a dirty checking.

In order for the digest cycle to be execute $apply(fn) has to be run, this is how you enter the Angular world from JavaScript. How does $apply(fn) get called (taken from AngularJs integration with browser):

The browser’s event-loop waits for an event to arrive. An event is a user interaction, timer event, or network event (response from a server). The event’s callback gets executed. This enters the JavaScript context. The callback can modify the DOM structure. Once the callback executes, the browser leaves the JavaScript context and re-renders the view based on DOM changes. Data Binding

In order to achieve two-way binding, directives register watchers. For a page to be fast and efficient we need to try and reduce all these watchers that we create. So you should be careful when using two-way binding - i.e. only use it when you really needed. Otherwise use one-way:

Here it is quite obvious that the title of the page probably won’t be changed while the user is on the page - or needs to see the new one if it is changed. So we can use :: to register a one-way binding during the template linking phase.

The main issues I’ve seen with explosions of watchers are grids with hundreds of rows. If these rows have quite a few columns and in each cell there is two-way data binding, then you’re in for a treat. You can sit back and wait like in modem times for the page to load!

Asynchronous method invocation

Asynchronous Method Invocation (AMI), also known as asynchronous method calls or asynchronous pattern is a client-side support that doesn’t block the calling thread while waiting for a reply. Instead, the calling thread is notified when the reply arrives. Polling for a reply is an undesired option.

Alternatives are synchronous method invocation and future objects.

Scala Future and C# async/await

C# Example: async/await

The following Windows Forms example illustrates the use of await in an async method,

WaitAsynchronouslyAsync. Contrast the behavior of that method with the behavior ofWaitSynchronously. Without an await operator applied to a task, WaitSynchronously runs synchronously despite the use of the async modifier in its definition and a call to Thread.Sleep in its body.

private async void button1_Click(object sender, EventArgs e)

{

// Call the method that runs asynchronously.

string result = await WaitAsynchronouslyAsync();

// Call the method that runs synchronously.

//string result = await WaitSynchronously ();

// Display the result.

textBox1.Text += result;

}

// The following method runs asynchronously. The UI thread is not

// blocked during the delay. You can move or resize the Form1 window

// while Task.Delay is running.

public async Task<string> WaitAsynchronouslyAsync()

{

await Task.Delay(10000);

return "Finished";

}

// The following method runs synchronously, despite the use of async.

// You cannot move or resize the Form1 window while Thread.Sleep

// is running because the UI thread is blocked.

public async Task<string> WaitSynchronously()

{

// Add a using directive for System.Threading.

Thread.Sleep(10000);

return "Finished";

}

Scala Future

import scala.util.{Success, Failure}

val f: Future[List[String]] = Future {

session.getRecentPosts

}

f.onComplete {

case Success(posts) => for (post <- posts) println(post)

case Failure(t) => println("An error has occured: " + t.getMessage)

}

Scala Future VS C#: async/await

C# aync/await: the asynchronous method is NOT running in another thread, so you don’t have to worry about shared resources. You lose the benefit of this asynchronous task being run, for instance, on another CPU core, but, you still gain the benefit of not having to wait for network/disk I/O.

Scala Future: A Future is the placeholder for the returned value of a method that will be executed asynchronously. You can treat it like a return value, passing it around to things that will need the return value. If you want to add two Future[Integer] objects together, you can compose them into another future that will have the combined result.